|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

(The article was originally published in OPEN Magazine on December 20, 2024. Views expressed are personal.)

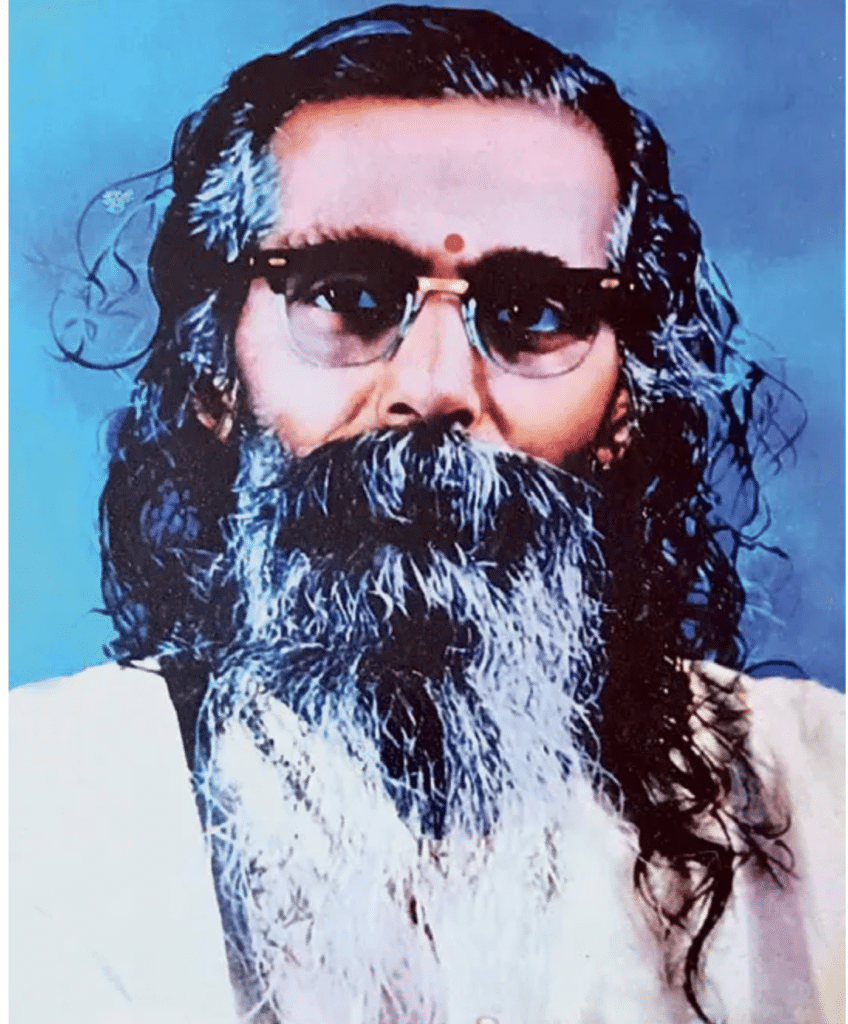

THE RASHTRIYA SWAYAMSEVAK SANGH (RSS) HAS entered its 100th year this October. Started in 1925 by a politically and socially motivated freedom fighter from Nagpur, Keshav Baliram Hedgewar (fondly known in RSS as “Doctorji”), the organisation has the unique record not only of entering its centenary without ever experiencing any divisions, but also demonstrating continuous growth and expansion. At 100, the organisation still looks young and exemplarily agile, with millions of cadres running hordes of activities with military-like precision and missionary-like dedication. And all this without any fuss, and away from the glare of media and publicity.

It will be instructive to understand the vastness of RSS in numbers and data. The daily meeting activity, called shakha, unique only to RSS, is held in over 75,000 places in the country. Its supporters hold weekly meetings in another 25,000-30,000 places, making it a humungous non-governmental organisation having regular meetings at more than a lakh places. Its reach can be easily understood from the fund collection drive it undertook in 2023 for a month for the construction of the Ram Janmabhoomi temple, during which period around 5 million RSS cadre spanned out into more than 5.8 lakh towns and villages and reached out to almost 200 million households, which account for two-third households in the country. On the day of the inauguration of the Ram temple at Ayodhya in January 2024, RSS held programmes across the country in which a record 280 million people participated. These numbers represent only a part of the RSS’ spread. Over the decades, the organisation has spawned more than 40 allied organisations, popularly known as the Sangh Parivar, which too have enormous reach and influence in the country.

Yet, the organisation remains an enigma to many. “The RSS is difficult to understand and easy to misunderstand,” quipped Walter K Andersen, an academic from the US who authored a book on the history of the organisation in 1983 by the name RSS: The Brotherhood in Saffron. The only other organisation that comes to mind for comparison is the International Committee of the Red Cross, or simply the Red Cross, that continues to be engaged in service activities across the world for over 160 years. But unlike RSS, Red Cross’ mandate is limited to relief and rehabilitation of the victims of natural and man-made disasters. The Red Cross relies mostly on the support of various governments and multilateral bodies, besides private charity and philanthropy.

RSS, on the other hand, runs its humungous machinery on a completely voluntary basis, with no salaried employees, nor any public funding. The entire edifice was built in the last 100 years by the participants of the organisation, called the swayamsevaks. Founder of RSS, Hedgewar, was categorical from the beginning that the swayamsevak would be a distinct type of activist of the organisation who cannot be called even a volunteer, much less a member. For that matter, RSS is an open organisation without any formal membership, a unique characteristic that baffles many. Swayamsevaks are those citizens of the country who come forward to dedicate their body, mind, and money—tan, man, dhan in RSS terminology—in the national cause without expecting anything in return.

It is pertinent in this context to quote Swami Vivekananda to explain the mindset of a swayamsevak. “Mark me, then and then alone you are a Hindu when the very name sends through you a galvanic shock of strength. Then and then alone you are a Hindu when every man who bears the name, from any country, speaking our language or any other language, becomes at once the nearest and the dearest to you. Then and then alone you are a Hindu when the distress of anyone bearing that name comes to your heart and makes you feel as if your own son were in distress. Then and then alone you are a Hindu when you will be ready to bear everything for them, like the great example I have quoted at the beginning of this lecture, of your great Guru Govind Singh. Driven out from this country, fighting against its oppressors, after having shed his own blood for the defence of the Hindu religion, after having seen his children killed on the battlefield—ay, this example of the great Guru, left even by those for whose sake he was shedding his blood and the blood of his own nearest and dearest—he, the wounded lion, retired from the field calmly to die in the South, but not a word of curse escaped his lips against those who had ungratefully forsaken him! Mark me, every one of you will have to be a Govind Singh, if you want to do good to your country,” exhorted the saffron saint in one address. The swayamsevaks are Hindus in Vivekananda’s mould.

INCIDENTALLY, SWAMI VIVEKANANDA’S life and teachings play an important role in the life and growth of RSS. The concept of “Hindu Rashtra” is largely drawn from Vivekananda’s teachings about the civilisational and cultural identity and oneness of the ancient nation of Bharat, and not necessarily from any religious or sectoral identity prism. The second chief of the organisation, called the Sarsanghachalak, Madhav Sadashiv Golwalkar, famously known as “Guruji”, was an ordained monk of the Ramakrishna Order started by Swami Vivekananda.

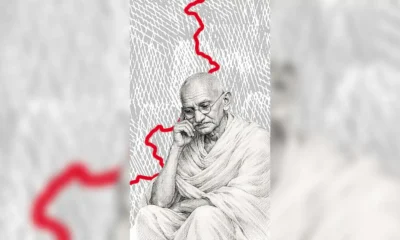

Founder of RSS, Doctorji, was a political activist of the early 20th century. He initially dabbled with revolutionary politics against the British for some time before joining the Congress movement in the early 1900s, inspired by the Maharashtra stalwart Lokmanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak. The revolutionary streak in him did not endear him to Gandhi, the rising star of the Congress movement in the post-Tilak era of the 1920s, and his politics of accommodation, compromise and emphasis on nonviolence. However, as a committed leader of the Independence movement, Hedgewar always followed the leadership of Gandhi with due respect and continued to participate in various activities under the banner of Congress. He played an important role as the local organiser when the All India Congress Committee held its annual session at Nagpur in 1920. He went to jail participating in the Forest Satyagraha upon a call given by Gandhi in 1930. He encouraged all, including those joining his budding organisation, to actively participate in the movement for the country’s freedom.

But his shrewd political mind convinced him that the freedom achieved through compromises, without ridding the nation of the root cause of its loss in the first place, would be weak and soon become redundant. He believed that the disunity within the national society, both political and social, was the root cause of slavery. While social divisions like caste, sect and religion led to weakening of the society in the face of the onslaught of the proselytising Semitic religions, political disunity and quarrels among various rulers due to their corruption, greed and lack of character resulted in the surrender of the sovereignty of the country to the foreign invaders. Hedgewar’s prescription was to create a national society strong in personal character, imbued with a strong sense of national pride, that would be the basis of an enduring unity of an otherwise diverse society. It was such a prescription that had led to Hedgewar starting RSS in 1925. It was essentially a socio-political mission catering to the need of the hour, inspired largely by the works of reformers like Tilak, Sri Aurobindo and VD Savarkar, that formed the core of the organisation under Hedgewar. The swayamsevaks during the initial years were asked to take a pledge that included “securing independence for Bharat” as one of the objectives.

HEDGEWAR’S SUCCESSOR, Guruji Golwalkar, added a new dimension to it after his ascension to the role of the Sarsanghachalak in 1940. As the country moved closer to securing independence, Golwalkar sought to reduce the political content and introduce religious and spiritual components into the organisation’s vision and mission. As mentioned earlier, Golwalkar was an ascetic trained in the Ramakrishna Order of Swami Vivekananda. He held a firm view that while culture and religion are all-encompassing and uniting, politics in the Hindu scheme of things is only a minor part of social life, often coming with the potential to divide. Thus, under Golwalkar’s stewardship, this socio-political organisation acquired the character of a socio-cultural body.

This transition into non-political character was not easy. Vivekananda started Ramakrishna Mission with a unique programme akin to the one he witnessed in a Catholic ecclesiastical group of Jesuits. Jesuits were dedicated Catholic propagandists, but different from the ordained priests. They were not confined to the churches and monasteries. They followed the path of teaching and service to spread the Christian concept of love. Vivekananda appeared to have been influenced by their modus operandi, first in Goa during his interaction with Jesuit institutions, and later during his travels in America. He even delivered a couple of lectures praising those activities of love and universal religion as against the fundamentalist and sectarian interpretations of other Christian denominations.

Ramakrishna Mission, started by Swami Vivekananda, followed a distinct approach. It did not create gurus who sit in temples and monasteries while the faithful are expected to come searching for religion. The monks of the Mission were mandated to take the universal dharmic message of love and inclusion to the nooks and corners of the country and teach and serve the people. Guruji was a product of that Order. One of the early dimensions he added to the Sangh work was the “pracharak” system, a band of monk-like activists similar to the monks of his erstwhile Order, who would dedicate themselves to the spreading of the socio-cultural work of RSS. Described once as “white-clad sanyasis” by Swami Chinmayananda, one of the great gurus of the Sanatana Dharma, the pracharaks became the sinews of the organisation, building it brick by brick and moulding it into a vast socio-cultural behemoth.

Hedgewar’s active role in the freedom movement had resulted in creating a perception about the political mission of RSS. It began in the 1930s itself with the British administrators and their camp followers among native officials seeking to impose various types of restrictions on its activities. Guruji tried consciously to build an edifice of non-political character, yet the challenge remained daunting in the decade of the 1940s. Leadership of independent India, led by stalwarts like Jawaharlal Nehru and Sardar Patel, too, viewed RSS from a political prism. Nehru saw in it a challenge to his secular ideological politics and sought to crush it using the murder of Gandhi in 1948 as an excuse. Patel as the home minister understood that the organisation had nothing to do with the alleged crime, but preferred it to be a part of Congress strengthening his leadership, rather than maintaining an independent identity. Guruji’s steadfast refusal to turn his organisation into a political instrument had resulted in temporary trouble for the organisation in the form of continued ban and incarceration of a large number of its cadre.

Guruji’s firm apolitical stance had resulted in some turmoil within, too, with leaders like Balasaheb Deoras, the third chief of the organisation, and his brother, Bhaurao Deoras, differing on the issue and temporarily leaving the organisation. The brothers had joined the organisation under Hedgewar and imbibed the socio-political spirit of it, and strongly believed that the organisation should be groomed on those lines after independence too. But soon, all agreed that the path chosen by Guruji was more credible and long term, and the brothers, too, returned to the alma mater and rose in rank to occupy high positions in the later decades.

Guruji did not detest politics. He, in fact, loaned important Sangh functionaries like Deen Dayal Upadhyaya, Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Lal Krishna Advani for political work under Syama Prasad Mookerjee when the latter started the Bharatiya Jana Sangh in 1951, a practice that continues to this day. He constantly guided the rise of the new party committed to political goals that were in line with the socio-cultural mission of RSS. However, he also assiduously maintained the nature and texture of RSS as non-political. During that period, he himself, and other functionaries, were able to build cordial ties with leaders across the political spectrum.

Golwalkar’s emphasis on the socio-cultural as against socio-political, helped the organisation reap enormous goodwill. Despite initial ideological differences, Nehru found RSS to be virtuous enough to march shoulder-to-shoulder with the Indian Army at the Republic Day parade in 1963. Over 2,500 RSS volunteers had participated in the marchpast upon the invitation of the government. Lal Bahadur Shastri sent a special plane to invite Golwalkar to Delhi to discuss the India-Pakistan war of 1965. When Indira Gandhi set up a high-powered committee in 1967 to examine the issue of a national ban on cow slaughter under AK Sarkar, retired chief justice of the Supreme Court, that committee included Golwalkar too. Golwalkar’s demise in 1973 was condoled in Parliament. Indira Gandhi paid her tribute, saying, “Shri Golwalkar, an eminent personality who was not a member of the House, is no more. He held a respected position in national life by his force of personality and the intensity of his conviction, even though many of us could not agree with him.”

HOWEVER, AS THE organisation grew in strength, new challenges started posing serious dilemmas before the leadership. The Sarsanghachalaks had to endure three important dilemmas—one, political; two, ideological; and three, organisational. I limit myself to the political dilemma in this article.

The political dilemma that haunted Golwalkar immediately after independence returned to bother the organisation in the post-Golwalkar era once again. For an organisation whose “pind”, or the essential core, was socio-political, developments like the Emergency of 1975-77 and the Ram Janmabhoomi movement of 1980s were enough provocation to shed the socio-cultural avatar and return to the Hedgewar era activism. At the same time, the newly formed Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which was home to many swayamsevaks, threw new challenges as it rose in power and influence.

Unlike the Jan Sangh, the newly formed BJP started attracting many new leaders with no RSS affiliation. When the new party officially adopted Gandhian Socialism as its ideology at the time of its formation in 1980, many in RSS squirmed with disbelief. Some irate leaders even proclaimed that the organisation was not “permanently wedded to any political party”. Results of the 1984 Parliament elections, in which BJP was decimated, with even stalwarts like Vajpayee losing, gave fodder to the rumour mills that the Sangh had dumped BJP for good. However, BJP’s decision under the Vajpayee-Advani leadership in 1989 at Palanpur in Himachal Pradesh to throw its weight behind the Ram Janmabhoomi movement had retrieved the situation.

As BJP grew in strength and influence through the 1990s and the new century, this epistemic dilemma started increasingly haunting the Sangh cohort of organisations. Should national interest be determined by the government of the day manned by the swayamsevaks, or should the organisation itself step in to determine what constitutes national interest from the ideological prism? This conflict kept surfacing again and again in the last two decades. The Vajpayee government during 1998-2004 faced severe criticism from sections of Sangh Parivar, with one senior leader even asking the Vajpayee-Advani duo to step down allowing the next generation of leaders to take over. On its part, the BJP leadership too had witnessed serious churning within, with some senior leaders going to the extent of suggesting that the party should chart an independent course.

In all these difficult situations, the RSS leadership has demonstrated astuteness and ensured that its socio-cultural character remained intact, while the socio-political agendas were left to the swayamsevaks in BJP. All the RSS chiefs after Golwalkar, from Balasaheb Deoras to Rajendra Singh to KS Sudarshan to Mohan Bhagwat, had to endure this dilemma. They all handled it with great aplomb and maintained the course set by Golwalkar.

There are two types of ideological political models in the world. One is the Communist Party of China (CPC) model, in which, the party is everything. It controls all the wings—students, peasants, workers, media and even culture. Party is even above the government. Party determines everything and the government’s role is merely to implement it. Communist parties in different countries, and some others like JVP in Sri Lanka, follow this model. The other model was practised in the UK by the British Labour Party. A party created by the labour unions, it was under their total control until late-20th century. However, the hold of the labour unions in the affairs of the British Labour Party is gradually diminishing. Currently, the unions elect less than 50 per cent delegates to the party conference and their voting power has been reduced to one-third.

RSS has thus far presented a third model, wherein it relied on its swayamsevaks for carrying the mantle forward in all walks of national life, including and importantly, in politics, without ever attempting to control them directly. Its faith in its own cadre, which rose to occupy high positions of the political leadership, prompted it to allow sufficient freedom to the party.

The rise of BJP to an unassailable position in the country under Prime Minister Narendra Modi is undoubtedly one of the golden chapters in the history of the 100-year-old organisation. The swayamsevaks are in a position today to implement the agenda of national interest using the support and goodwill they enjoy from the masses of the country. The track record of the last 10 years is ample evidence of the vision that every swayamsevak imbibes in RSS being turned into commendable action.

But this phenomenal rise of the popularity of the political activity run by the swayamsevaks under Narendra Modi brings back the epistemic dilemma. Misleading debates over whether a given electoral victory of the party was because of the swayamsevaks in the party and outside or because of RSS as an organisation, create a moral dilemma. The political journey of the Sangh movement ran on the four wheels of ideology, leader, cadre and Parivar. Ideology being a constant, the leader always carried the major burden, while cadre and Parivar brought the necessary heft. Leader-centrism may not harm the party because politics revolves around leadership. But politics-centrism among the RSS cadre may harm the Sangh. It calls for tremendous understanding about the complementarity and humungous patience and positivity in both the Sangh and BJP leadership to ensure that the socio-political and the socio-cultural do not cross each other’s paths, and do not step on each other’s toes.

After all, using the age-old Sangh analogy, the two rails—Parivar and Party—together build the track on which the vehicle of national interest traverses smoothly. They must maintain their determined distance. For a disaster to be averted, they should neither attempt to come closer, nor drift apart. At the stroke of its centenary, this will be the most testing challenge for the Parivar leadership.