|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

(The article was originally published by Indian Express on April 22, 2023 as a part of Dr Madhav’s bi-weekly column titled ‘Ram Rajya’. Views expressed are personal.)

It was afternoon time on December 23, 1926, in Delhi. Swami Shraddhanand, a senior Congress leader and a colleague of Gandhi, had just returned from a long trip and retired to his room at Naya Bazar. He was suffering from pneumonia and resting in his room when at around 4 PM, a young man by the name of Abdul Rashid entered his house and insisted on having a word with the Swami. Dharam Singh, the attendant, was reluctant, but the Swami overheard the conversation and allowed the young man to come in. As Dharam Singh stepped out to fetch some water, Abdul Rashid pulled out a revolver and pumped bullets into the 70-year-old fragile body of the Swami from point-blank range. Shraddhanand died instantly.

The entire nation was shocked by the murder. Shraddhanand was, until a couple of years ago, rubbing shoulders with the Muslim leadership. He even championed the cause of Khilafat, going to the extent of telling Indian Muslims that it was a “now or never” fight for them.

When news of Shraddhanand’s murder reached Gandhi, he was shocked and condemned the dastardly act. But he refused to blame Rashid. He instead blamed those who created an atmosphere of hatred “where someone would lose his balance and resort to such an inhuman act.”

“It is we, the educated and semi-educated classes that are responsible for the hot fever that possessed Abdul Rashid. It is unnecessary to discriminate and apportion the share of blame between two rival parties,” Gandhi argued. “Today it is a Mussalman who has murdered a Hindu. We should not be surprised if a Hindu killed a Mussalman. God forbid that this should happen but what else can one expect when we cannot control our tongue or our pen?” he contended, indirectly blaming Shraddhanand for his “shuddhi” work.

Gandhi then referred to Abdul Rashid as a “dear brother”. “I purposely call him brother, and if we are true Hindus, you will understand why I call him so”, he said. “… I do not even regard him as guilty of Swami’s murder. Guilty, indeed, are all those who excited feelings of hatred against one another,” he insisted.

A few days later, on December 30, Gandhi again wrote in Young India: “I wish to plead for Abdul Rashid. I do not know who he is. It does not matter to me what prompted the deed. The fault is ours.”

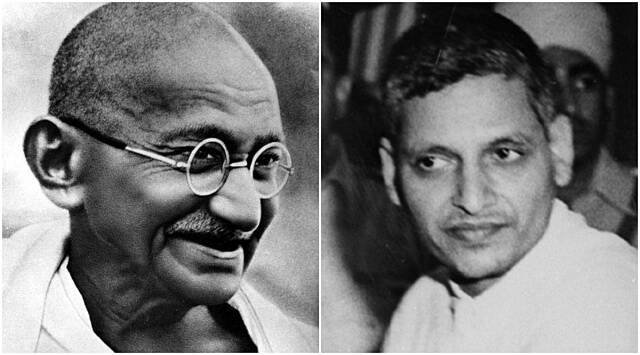

This episode is relevant to the recent controversy over some amendments in the NCERT textbooks. Some of those amendments related to the lesson on the murder of Gandhiji by Nathuram Godse. By Gandhian logic, Godse should have been a “dear brother”. But that will be an absurd argument. Godse’s crime was heinous. Neither the NCERT nor the ideological movement to which many in the Narendra Modi government belong condone Godse’s act.

The amended NCERT textbook continues to give details of Gandhi’s murder under the subheading “Mahatma Gandhi’s sacrifice”. It highlights Gandhi’s visit to riot-torn Kolkata on August 15, 1947, and his efforts to persuade both Hindus and Muslims to eschew violence.

But the problem with the said lesson was that it described Godse as a “Hindu extremist”, a “Brahmin from Maharashtra”, and the editor of a “Hindu extremist newspaper”. The NCERT experts committee decided to remove those references and revised the text to state that: “Finally, on 30 January 1948, one such extremist, Nathuram Vinayak Godse, walked up to Gandhiji during his evening prayer in Delhiand fired three bullets at him, killing him instantly”.

There is a clique in India for whom Gandhi is their bread and butter. That clique started raking up a controversy that the truth about Gandhi’s murder is being erased by the Modi government for ideological reasons.

Does the clique want that our children should be taught about “Hindu extremists”? Then why not also about “Muslim extremists”, “Christian extremists” and others? Did they not tell us ad nauseam that terrorism and extremism have no religion? Would Gandhi have approved of it, because, according to him, “guilty, indeed, are all those who excited feelings of hatred against one another”?

Another objection by the clique was to the deletion of references to the government’s ban on the Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh (RSS) following Gandhi’s assassination. The deleted sentences read, “The Government of India cracked down on organisations that were spreading communal hatred. Organisations like the Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh were banned for some time. Communal politics began to lose its appeal.”

Gandhiji’s insistence was on satya — truth. This now-deleted paragraph told only a half-truth. It is true that the RSS was banned by the government on the allegation of involvement in Gandhi’s murder. But the lesson refuses to inform students of the truth that the ban was illegal as the courts didn’t find any evidence of such involvement.

In fact, the ban was more a result of Jawaharlal Nehru’s antipathy towards the RSS than any real criminality on its part. In a letter to Vallabhbhai Patel on February 26, 1948, Nehru insinuates that not enough was being done to implicate RSS men in the case. Stung by Nehru’s tone, Patel sends a detailed reply the next day, on February 27, 1948, categorically asserting that “I have kept myself almost in daily touch with the progress of the investigation in Bapu’s assassination case. …….. It also emerges from these statements that the RSS was not involved in it at all.” Yet the ban was not lifted till July 1949.

None of these facts were being taught to the children. So much for the Gandhian idea of “truth”.

History remains a contested topic. “History will be kind to me for I intend to write it,” quipped Winston Churchill once. But facts are sacred. Indian history has been a prisoner of a clique of leftist historians for many decades. They quiver when their hegemony is challenged by facts, as the NCERT did.

As for Gandhiji, he belonged to all Indians. No one can create an exclusive club for him.