|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

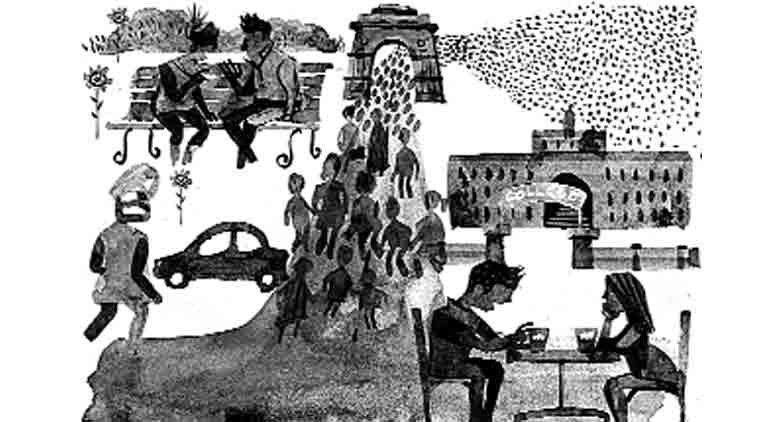

Delhi has grown exponentially in the last couple of decades as a result of universal factors like migration, industrialisation, urbanisation. Delhi has always been a city of migrants. In the wake of Independence, it witnessed the influx of massive numbers of refugees who came from the newly born state of Pakistan. Post Independence, the city was built largely by these refugees, who came mostly from Punjab, imbuing it with an initial identity that was Punjabi.

Then Delhi became the capital of the new government of India. As the seat of political power, the city attracted a large number of government employees from all parts of the country. It also became home to politicians from different states. Thus, the city became a political and government bastion.

In the last two decades, the processes of globalisation, industrialisation and urbanisation have added waves of migration to the city. Many of these people were economic migrants who came to the capital in search of opportunity and employment. They came mostly from Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and West Bengal (though it is alleged that it was actually Bangladesh). Thus, in the late 1990s, the city’s character began to change from a Punjabi-dominated city to a city dominated by the Purabiyas, people from eastern UP and Bihar.

These various identities continue to influence public life in Delhi. Six decades after Independence, the city is the political nerve-centre of the country. Thousands of aspiring and established politicians throng the city, lending it an extremely political colour. Of late, politics has become a subject of derision thanks to a sustained smear campaign. Of course, there are good politicians and bad — but this is also true of every other profession. What is notable is that, in the last few years, the political identity of the city has also undergone a major transformation. Many young people have entered the political arena. The city’s seven Lok Sabha MPs are all young by the standards of Indian politics. In city politics, too, the dominant role is being essayed by young leaders.

Delhi today has emerged as a city of activism and hope, with an omnipresent youthful energy. A new socially and politically conscious generation is changing the contours of public life in the city. True, Delhi is notorious today for the high incidence of violence against women, and is labelled the “rape capital”. The crime rate in general is also high. But the city has also witnessed huge public mobilisations against corruption and crimes against women. Young Delhi knows how to demand accountability.

This is not a rowdy youth. Instead, it is aspirational, creative and, most importantly, socially conscious. There was

a time when people thought that urbanisation was bad. Now though, cities have become the lifeline for creative and aspirational young men and women, educated or not.

The city is not just about politics, though. It has an underbelly that is anything but political. Mahatma Gandhi used to say that India lives in villages. What he meant was that the culture, traditions and ethos of our land are better preserved and protected in villages, which is largely true. Equally true is that the migrants who come to Delhi or any other city bring with them their cultures and traditions, too. That is why Delhi is in celebration mode all through the year. From the Tamil Pongal to the Malayali Onam and the Ganesh Chaturthi of the Marathis, from the Gujarati Garba to Holi and Durga Puja — when is there no celebration in Delhi?

Young men and women drive life in the city today. There is no cause for concern over their youthful activities, the clothes they wear or the places they visit. We must have faith in them and guide them, because they are no less idealistic than any previous generation of young people. We may find them at a bar or a coffee bar; watch them closely and they’ll likely be talking about a Narendra Modi or an Anna Hazare, discussing corruption and cursing social evils.

They have dreams in their eyes and ideas on their minds. Where we have failed is in giving them direction. We have to create excellent educational institutions in Delhi and improve the standards of our schools and colleges. We have to encourage sports in a big way. We have to create a conducive atmosphere for non-governmental activism. We have to allow youngsters to take over public life in the city. Perhaps we could hand over to them public spaces like parks and playgrounds and ask them to manage them?

Swami Vivekananda returned to India in 1897 after a four-year sojourn in the West. He reached Colombo and then travelled across the length and breadth of the country for over a year, ending his journey in Almora. He addressed hundreds of meetings during his year-long travel. He began his address at almost all of them by invoking youthful energy: “Oh, my dear young men and women of Madras! All my hopes lie on you,” he would say. Can we also say that

to our youth?

The writer is BJP vice president and general secretary