|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

There were many who had disagreements with Gandhi… but to kill him needed not just difference of opinion, but a certain type of hatred borne of extreme frustration

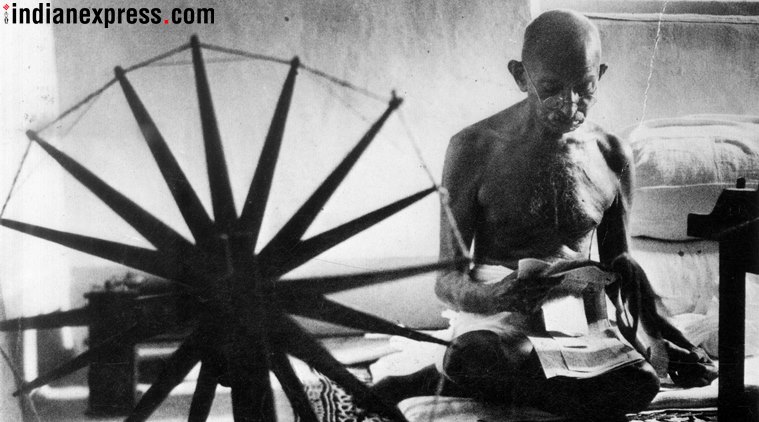

On the evening of January 29, 1948, Mohandas Gandhi told his grand-niece, Manu: “If an explosion took place… or someone shot at me and I received his bullet on my bare chest, without a sigh and with Rama’s name on my lips, only then you should say that I was a true mahatma”. Twenty-four hours later, he stood face-to-face with a young man called Nathuram Godse.

Gandhi was late for the sermon that evening. Sardar Patel had come to discuss some issues. This became a routine during Gandhi’s stay at the Birla House. Jawaharlal Nehru too used to visit him almost every evening. Although Gandhi relinquished his primary membership of the Indian National Congress some 14 years earlier, he would always be consulted on important issues.

Gandhi was rushing towards the garden, supported by Manu and Abha, the two-grand nieces whom he used to call his “walking sticks”. Godse folded his hands and said namaste. Gandhi stopped. Suddenly, Manu was pushed to the ground. Nathuram pumped three bullets into Gandhi’s bare chest and stomach. “Hey Ra…ma! Hey Ra…” — this is what Manu claimed to have heard in a feeble voice. A Sikh gentleman following Gandhi too confirmed that the words of prayer came out from his lips. Gandhi was dead, his mahatmahood having been established.

Gandhi’s physical elimination was a result of the pent-up anger and frustration of a few misguided youths over what they perceived as his policy of Muslim appeasement. The ultimate provocation for them was his fast that January that had forced the Nehru cabinet to release funds to the newly-formed state of Pakistan. Those funds were withheld out of the suspicion that Pakistan would misuse them against India.

There were many who had disagreements with Gandhi, Subhash Bose and V D Savarkar among them. Even Nehru had serious difference of opinion with Gandhi. But to kill him needed not just difference of opinion, but a certain type of hatred borne of extreme frustration. “A most severe austerity of life, ceaseless work and lofty character made Gandhiji formidable and irresistible,” admits Godse in his final testimony before the court. Gandhi was no doubt formidable and irresistible. Nehru once said of him: “The essence of his teaching was fearlessness and truth and action allied to these. The voice was somehow different from others. It was quiet and low, and yet it could be heard above the shouting of the multitude; it was soft and gentle, and yet there seemed to be steel hidden away somewhere in it. Behind the language of peace and friendship, there was power and the quivering shadow of action and a determination not to submit to a wrong.”

Gandhi had a premonition about his impending death. Madanlal Pahwa attempted a bomb attack on January 20 at the Birla House. Between that day and the fateful day, Gandhi had talked about his death dozens of times. But he would steadfastly refuse security. For him, that would have been akin to violating ahimsa. People called him “Bapu” — a father-figure. He had immense trust in the people, unlike today’s leaders: “If my own children want to kill me, how can I stop them.”

He was betrayed by those who called him Bapu and then eliminated physically, a heinous crime. Others too, who also called him Bapu and Mahatma, betrayed his principles.

On the fateful morning, Gandhi handed over the final draft of his future plan for the Indian National Congress, which he had dictated to Mirabehn a day before, to his aide Pyarelal. “… the Congress in its present shape and form, i.e., as a propaganda vehicle and parliamentary machine, has outlived its use”, he declared, adding “For these and other similar reasons, the AICC resolves to disband the existing Congress organisation and flower into a Lok Sevak Sangh.”

In fact, Gandhi had called for a meeting at Sewagram in February to discuss the plan. The meeting did take place, minus Gandhi. Nehru categorically rejected Gandhi’s plan. “Congress has now to govern. So it will have to function in a new way, staying within politics”, he insisted. The lure of power overtook the ideals of service. Thus came the other betrayal.

But that was not to be the end. “I am not going to keep quiet even after I die”, Gandhi had once declared. His lifetime of work had a “constructive” component, besides the political. Led by Gandhians like Vinoba Bhave, the constructive work had gone on. Gandhi insisted that it be “kept out of unhealthy competition with political parties and communal bodies”. Bhave had never met Nehru while Gandhi was alive. In the first meeting at Sewagram after Gandhi’s demise, he tells Nehru that he wouldn’t want anything from the government; rather he would want to help Nehru if possible. Gandhians continue to strive for the goal of attaining “social, moral and economic independence in terms of its seven hundred thousand villages” by remaining below the radar, unlike present-day NGOs that meddle in politics. Gandhian ideas continue to influence societies in many parts of the country and the world.

“Gandhi bequeathed an example of constant striving, a set of social values, and a method of resistance, one not easily applied to an India ruled by Indians”, laments Pulitzer-winning author Joseph Lelyveld in his book Great Soul.

(The article was originally published in Indian Express on January 30, 2019. Views expressed are personal)